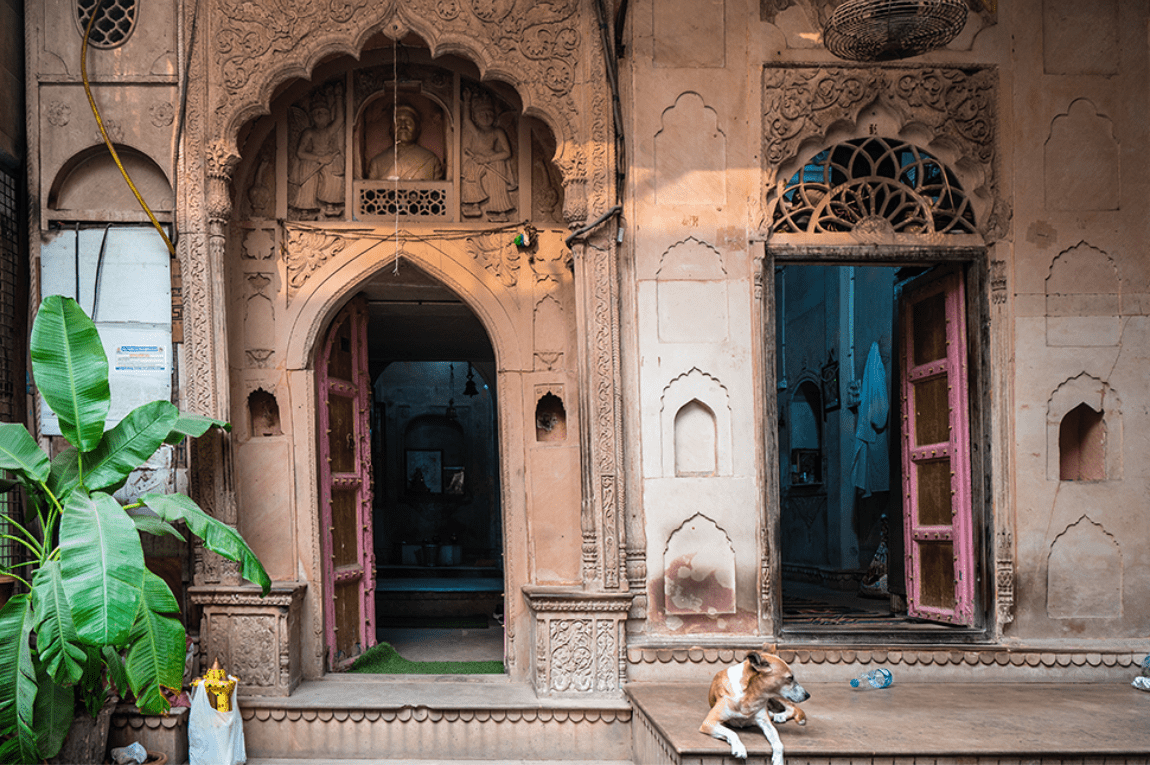

As the old saying goes, “Dilli saat baar ujadi aur basi.” (Delhi has been rebuilt seven times), the city of Delhi has been populated and repopulated; built, destroyed, and rebuilt, several times over. The seven historical cities of Delhi include: Lal Kot, Siri, Tughlaqabad, Jahanpanah, Firozabad, Shergarh and Shahjahanabad. Shahjahanabad was the last of these seven historical cities of Delhi, and served as the Mughal capital from the reign of Emperor Shahjahan. Even after its political collapse and its succumbing to British rule pre-independence, Shahjahanabad (Purani Dilli) lives on as the heartland of a vibrant community and a cultural heritage site.

BACKGROUND:

During his 12th regnal year, Emperor Shahjahan decided to change his capital from the city of Agra, and built his new capital, the walled city of Shahjahanabad (Old Delhi/ Purani Delhi). The construction of the city was completed in 1648. Shahjahanabad (named after the emperor) was developed around his palace, the Lal Quila or Red Fort of Delhi. Initially, Shahjahanabad was meant to consist of only a small area surrounding the fort. However, by the eighteenth century, the city was further developed by the ruling elites along with the common people. At its zenith, the city was bustling with artisans, trade and commerce. It was the abode of the wealthy jagirdars, merchants and also the commoners.

According to Stephen Blake, Shahjahanabad was surrounded by a massive 27 feet high and 12 feet thick stone wall, about 3.8 miles long, and enclosed an area of about 1500 acres. The city had several gates, including Lahore gate, Ajmere gate, Turkman gate, Delhi gate, Moor gate, Kabul gate and Kashmere gate; all of which were arched entrances which served as watchposts for city guards. Other gates like Raj Ghat Gate, Khairati gate, Kela Ghat Gate and Nigambodh Gate were situated by the river Yamuna.

The land that was situated to the west of the palace was allotted to the nobles and rich merchants through the allotment of jagirs or land grants. Interestingly, the proximity to the palace was an indicator of social standing, with the residence of people of common origins placed around the periphery. In the late 17th century, a surrounding wall was added to the Shahjahanabad, and the city took on its definitive shape.

LAYOUT/FEATURES:

According to scholar Rory Fonseca, the city is fundamentally structured around 6 architectural elements, namely- the Fatehpuri Masjid, private gardens (Bagh Begum Saheb), Chandini Chowk, the Jama Masjid, Faiz Bazar, and Kasi Hauz. The construction of the Fatehpuri Masjid was completed in 1650. Soon afterwards, the private gardens of the Begum of Sahjahan were built, slightly to the north of the pathway that led from the Lal Qila to the Fatehpuri Masjid. Chandini Chowk served as a market and the residence of merchants. Several important buildings like Sonehri Masjid, a police station (Kotwali), and karavan sarai were located along it. The Jama Masjid was another landmark which was completed in the 1650s. The Faiz Bazaar became the chief north-south route through the city in the later years. Lastly, the Kasi Haus, which was the main water reservoir, was situated at the intersection of four important bazaars.

These six landmarks along with the city gates were indicators of the hierarchy of the spatial distribution of the population, as well as the patterns of the street. The paths connecting the city gates to these landmarks gradually turned into regular streets, and later, important bazaars. Additionally, the less developed bazaars linked Chandini Chowk with the interior of the city, forming a network of streets and lanes. In addition to the larger gates, a number of small entrances known as “Khirkis” were also present, which provided passage for the residents to move in and out of the city.

The area to the north of Chandini Chowk were the villas, palaces and gardens of the aristocracy, with the exception of the northwestern sector. By the early 1700s, excluding the Lal Quila, the city contained three discernible sectors: the area north of Chandini Chowk where the nobility had its private estates, the Dariyaganj sector where the Europeans had settled, and the area south of Chandini Chowk which was inhabited by a heavy volume of residents.

The city was situated at the bank of river Yamuna. Contemporary sources mention descriptions of canals which were scattered across the city.One such canal was the Nahr-i Bahist (or Nahr-i Faiz), which provided water for canals, waterfalls, fountains, pools and gardens. Nahr-i-Bahisht was originally dug by Firoz Shah Tughlaq, and later on repaired and extended by Akbar. While reconstructing his new capital, Shahjahan ordered to repair the canal, yet again, and extend it even further, so that it could flow through the town, palace and Bazaars. Other sources providing water to the city included hauz or talab (tanks), wells, and Baoli (stepwells).

The prominent roads were wide and straight, and were linked to several minor streets (Kucha and Gali) which connected various parts of the city from different directions. These roads provided a framework around which the Mohallas and Katra were established. Mohallas and Katras were clearly defined residential areas, where socio-economic and commercial activities also took place. People usually settled according to common ethnic affiliations, making mohallas homogenous units. A traveller from the year 1793 mentions as many as 36 mohallas. During the early 19th century, Mirza Sangin Beg in his Sair-ul Manazil mentions 29 mohallas within the walled city and 37 mohallas or bastis outside the city. Although the mohallas were predominantly inhabited by people of a single community (caste, religion, profession, ethnicity etc.), there was no clear distinction between the houses of rich or poor, or between the residential or commercial areas. This feature would be enforced under the British. Additionally, separation between the residents of different communities did not mean a disconnection between them. There still remained a high degree of interaction between them.

Another important feature of these settlements was that of a “Chowk” (crossroad). A Chowk was a central, rectangular marketing place where several streets met. It was also a place of professional entertainment and also became a meeting place of sorts. Chowk were central spaces to community life and were often placed near a mosque or a temple. Chowks also had clear boundaries and belonged to specific groups or local communities. The land use changed around these areas, transitioning from a residential space to service-oriented shops like tea stalls, paan shops, or general stores.

Outside the walled city, the urban area comprised the Puras or the suburbs. These Puras, or ganj, emerged due to an overwhelming increase in the population , making it difficult to accommodate everyone within the walled city. Affluent men built their houses outside the wall and, in due course, named these Puras after themselves. However, these puras had no identity of their own and were included in the main town for the purpose of administration. An important function of the suburbs was to support the main city by providing useful services. Craftsmen and traders set up their workshops in these areas. Manufactured goods used by the people of the city were produced in these areas. Most wholesale markets were also found here.

Within the walled city, mosques were present in a large number. Similarly, other sacred places like tombs or Maqbaras were found in abundance. The existence of dargahs (shrines) and mazaars (tombs of saints) in the suburbs helped in maintaining the connectivity between the main city and the suburbs. Other places of worship included temples or mandirs, like that of Paras Nath, Jogmayaji, Kalkaji, Hanumanji and Makan Shitla.

DECLINE:

The city reached its peak during the reign of Aurangzeb. It reached a population of about 200,000 people. However, after Aurangzeb, the city experienced civil wars and invasions. Delhi was subsequently sacked twice; by Nadir Shah (1739) and by Ahmed Shah Abdali (1756).

After the death of Aurangzeb political uncertainty along with socio-economic disturbances defined the city. Under these conditions, a new form of poetry gained traction in the 18th century: the shahr-ashob. This form of poetry was meant to reflect lament for the city. For instance, after Nadir Shah’s invasion (1739), poet Mohammad Rafi Sauda wrote:

Jahanabad tu kab iss sitam ke qabil tha

Magar kabho kisi aashiq ka yeh nagar dil tha

Ke yun mita diya goya ke naqsh-e-batil tha

Ajab tarah se yeh bahr-e-jahan mein sahil tha

Ke jis ki khaak se leti thi khalq moti roll(Jahanabad you were never deserving of such tyranny

You were once the heart of lovers, many

It was erased like a wrong letter by destiny?

T’was a one such shore in the ocean of the world

From whose dust people used to pick pearls)1

In 1782, Mir Taqi Mir left Delhi for Lucknow, in the pursuit of employment. His Shahr Ashob depicts the economic collapse:

Marne ke martabe mein hain ahbaab

Jo shanasa mila so be asbaab

Tangdasti se sab bahaal kharab

Jis ke hai baal, tau nahin hai tanaab

Jiske hain farash, tau nahin hain faraash(My friends all seemed to death, near

Whoever I met had lost all possessions, once so dear

Poverty seems to be a cross all have to bear

If one had a thread, no rope was in sight here

If one had a carpet, there were none to roll it out)2

In his final years, Mir wrote expressing his regret over migrating from Delhi to Lucknow:

خرابہ دلی کا وہ چند بہتر لکھنو سے تھا

وہیں میں کاش مر جاتا سراسیمه نہ آتا یاںDesolate Delhi was far superior to Lucknow

If only I hadn’t rushed here and had died there instead.3

In 1803, following its victory over the Marathas in the Battle of Delhi, the English East India Company took over the control by making Delhi its protectorate. By the 19th century, however, extreme resentment grew towards the Company’s rule due to its unfair policies, recruitment practices in the Bengal Army, and the use of lard in the cartridges of the Enfield rifles. This unrest culminated in the revolt of 1857, when the sepoys of the East India Company rebelled against the British. They reestablished Bahadur Shah Zafar as their head and took control of Shahjahanabad. However, Delhi was recaptured by the British by September 1857. They demolished around 80 acres of the city to eliminate any potential threats to the English community. Delhi would stay under British control until the independence of India in 1947.

Conclusion:

Following the death of Aurangzeb, Shahjahanabad faced a gradual decline due to invasions, and eventually fell to British rule. The decline of the city meant a loss of power and wealth of the dominant groups. This also meant waning of the city’s prosperity. During the early 1900s, the British officially shifted their capital from Calcutta to Delhi. New Delhi was meant to be a contrast to Shahjahanabad and characterised by British ideals of a capital city. This area is now called Lutyens’ Delhi (named after its architect). However, despite its political decline, Purani Dilli was never completely abandoned by its people. Today, the area is known for its cuisine, markets, gardens, street food, and monuments. Old Delhi hosts hundreds of visitors every year. It is still an abode of various artisans and craftsmen. It is true that this area is facing challenges like growing traffic and congestion, and deteriorating infrastructure, Purani Dilli remains an important cultural heritage site. However, the preservation and restoration efforts to protect the monuments and infrastructure of this area are currently underway.

TRANSLATIONS:

- 1. https://www.sahapedia.org/shahjahanabad-shahr-ashob-poetry-and-the-revolt-of-1857

- 2. https://www.sahapedia.org/shahjahanabad-shahr-ashob-poetry-and-the-revolt-of-1857

- 3. Imaduddin. (2024). A poet’s lament for a lost city: ‘Dilli jo ek shahr tha aalam me intikhab.’ INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INNOVATIVE RESEARCH IN TECHNOLOGY, Volume 11(Issue 5), 843–847.

REFERENCES:

- Fonseca, Rory. “The Walled City of Old Delhi.” Ekistics 31, no. 182 (1971): 72–80.

- Kataria, Dinesh. “Planning Shahjahanabad, 1910s–1930s.” Social Scientist 47, no. 7/8 (554-555) (2019): 65–80.

- Ataullah. “MAPPING 18TH CENTURY DELHI: THE CITYSCAPE OF A PRE-MODERN SOVEREIGN CITY.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 67 (2006): 1042–57.

- Hasan, S. Nurul. “THE MORPHOLOGY OF A MEDIAEVAL INDIAN CITY A CASE STUDY OF SHAHJAHANABAD IN THE 18TH AND EARLY 19TH CENTURY.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 43 (1982): 307–17.

- https://www.sahapedia.org/shahjahanabad-shahr-ashob-poetry-and-the-revolt-of-1857

- Imaduddin. (2024). A poet’s lament for a lost city: ‘Dilli jo ek shahr tha aalam me intikhab.’ INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INNOVATIVE RESEARCH IN TECHNOLOGY, Volume 11(Issue 5), 843–847.

- https://delhidive.com/what-are-the-7-cities-of-delhi/