Introduction

Imagine if your grandmother’s comb could tell stories. Stories about not just her shiny white hair, but stories about royal patronage, mythical beasts, and artists who breathe life into dead buffalo horn. Welcome to Odisha’s horn art, a craft that’s as exquisite as it is endangered.

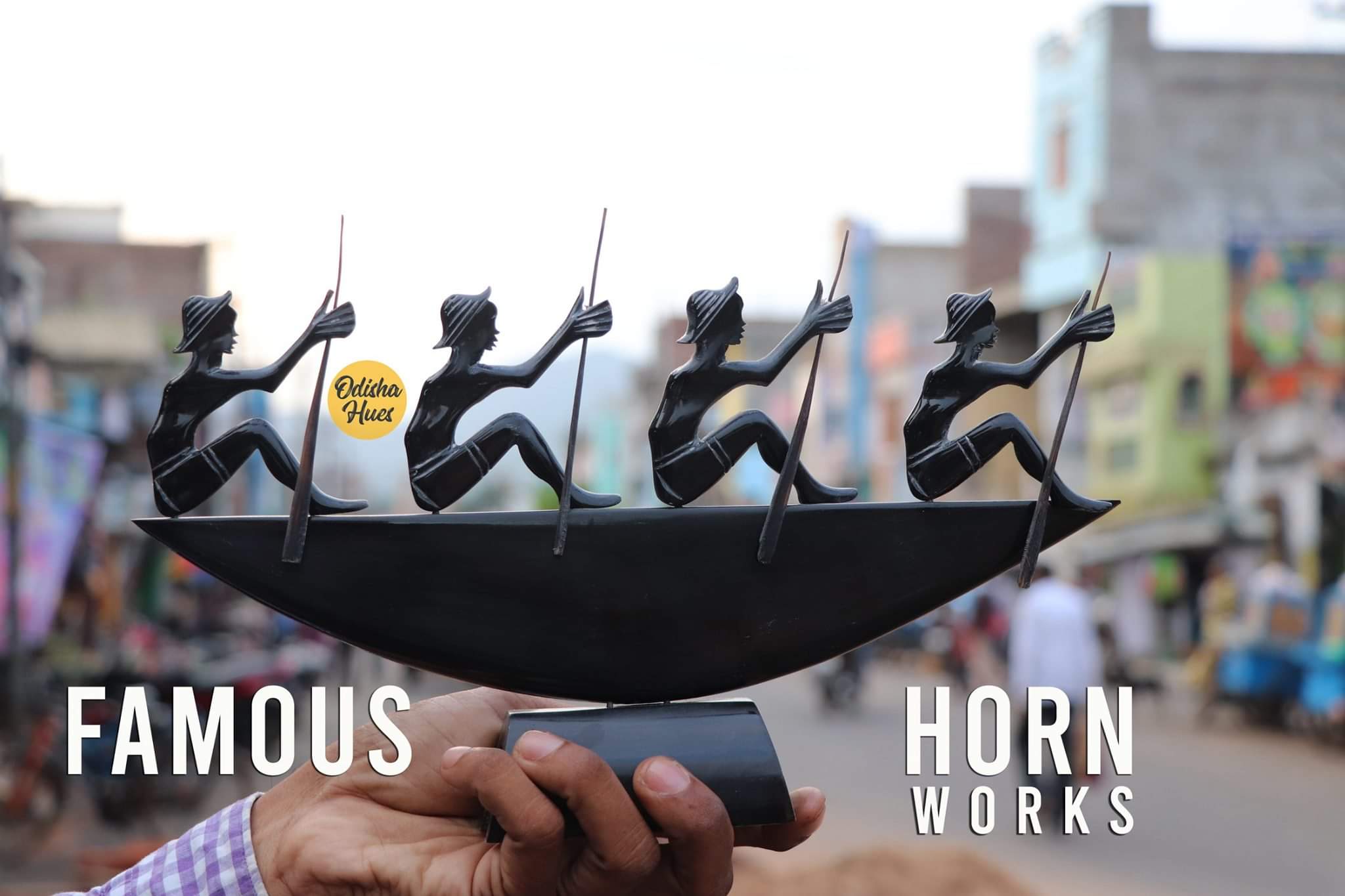

In 1901, The Statesman called them “excellent, graceful and original”. Initially made from silver, gold and ivory— and now, buffalo horn. The artisans of Paralakhemundi were not just makers; they were magicians. Peacocks perched, lovers rowed down in boats, and swans craned their necks– all from discarded bones and horn. This art represents the chaos of the universe tamed by human ritual– ideal for a material like horn, which is wild until it is carved.

Horns of Glory: The Maharaja’s Mandate

The story begins in Paralakhemundi, a princely town bordering Andhra with Maharaja Krushna Chandra Gajapati Narayan Deo of Paralakhemundi, the same man who dreamt Odisha into existence. It is believed that his interest in the art form began when he observed the Santhal, Oraon and Majira tribes using hollowed-out animal horns as containers during their festivals. He then commissioned Rao Sahib K.V. Apparao to carve a crane figurine from the horn, and it immediately exploded into a huge success. Sometimes, it just takes one person to see gold in what others believe to be garbage. The Maharaja was this person, and he helped institutionalise horn work in Paralakhemundi from mere craft to part of policy as a “hereditary occupation”– an early example of skill-based social security.

Six years later, Utkal Gourav Madhusudan Das – Odisha’s 1st lawyer and marketing visionary – took the baton. He set up Orissa Art Wares in 1898, taught artisans how to adapt to “modern tastes”, and exported horn, ivory, and bone art to Calcutta, Bombay, and even England. The Statesman was impressed. In 1901, it called them “graceful and original”.

Back then, around 200 families in Cuttack thrived on this craft. The roads of Thoriasahi, Ranihaat, and Manglabag echoed with the scraping sound of blade on horn.

Today? Only 13 artisans remain. 3 in Cuttack. 10 in Paralakhemundi. A centuries-old art form is now gasping for breath like a fish out of water.

Material Alchemy: From Horn to Hope

Unlike wood or stone, buffalo horn is light, translucent, and surprisingly malleable when heated up. The crafting process is both surgical and spiritual:

- Soaking and softening- Horns are boiled and sliced. The pungent smell emanating is part of the ritual.

- Heating and pressing- Pieces are flattened with wooden hammers and then pressed into desired shapes.

- Carving: Artisans use chisels and scalpels to carve intricate details like eyes and floral patterns.

- Polishing- the final piece is rubbed with dry leaf ashes or coconut oil till it shines like onyx.

What makes this art magical is that no two pieces are identical, since the process cannot be automated. When dyed, horn glows like stained glass. When left raw, it mimics antique ivory. And all this, without harming a single animal – the artisans only use naturally shed or post-mortem horn.

In today’s internet language? This would be called Ethical. Sustainable. Zero-waste. Pinterest-core.

Motifs: The Poetry of Horn

Horn art isn’t just about shape– it’s about storytelling. Odisha’s horn artisans draw inspiration from the natural world around them, their regional myths, and their folk beliefs. Let me take you through some of their signature motifs:

1. Sāra Paṅkhi (The love birds)

A pair of 2 or more birds, often swans or doves, are carved facing each other, their necks arched to form a heart— a universal shape of love. In Odia, sara means “mutual” or “together” and panki means “bird”. The motif stands for conjugal harmony or family love, as it sometimes features a mother bird with her chicks as well.

In weddings across Odisha, wooden or terracotta versions of these birds are used in rituals. The horn version however, is more than just symbolic. The curve of the horn lends a natural suppleness to the bird’s bodies. When polished, the feathers gleam like feathers wet with morning dew.

What’s unique is how each piece is different because each horn has a different grain and gradient. One piece may have black wings and amber eyes, another might have golden beaks– making no two love stories alike.

2. Makara Torana (Mythical Crocodile Arch)

The Makara, a mythical beast from Indian lore, is a combination of crocodile jaws, elephant tusks and a fish tail— a hybrid guardian at the gates of temples. It appears above temple doorways (called torana), in jewellery and on royal insignia. In Odisha, Makar Sankranti is named after this creature, marking both protection and transition.

In horn craft, the makara is carved like a crescent arch, with the makara’s gaping mouth forming the central curve, and snakes, waves and fish forming supporting tendrils. The result is a fluid structure that moves and ripples like water, unlike typical static stone carved versions.

3. Mayura (The Peacock)

Peacocks in Odia folk art are not just birds– they are celestial beings, often linked with Kartikeya (his vahana) and Saraswati, the goddess of wisdom. They represent beauty, intelligence and divine mystery.

In horn craft, the mayura is a tall, slim sculpture — with a body that curves like a question mark and a head that leans delicately forward. The tail, however, is its crown jewel. It bursts into radial layers, each feather finely etched with eye-shaped circles. When light hits it at the right angle, a translucent, bronze-green shine emerges, mimicking real peacock feathers. Unlike painted versions, the horn mayura offers depth (3D over 2D), changes appearance under sunlight, and lasts decades without fading.

4. Gaja Nauka (Elephant Boat)

Imagine this: A crescent-shaped boat carved from horn with its edges flaring forward. Perched atop it is an elephant, royally decorated, sometimes accompanied by a rider/parasol. The boat is detailed with fish scales, waves and serpentine patterns.

This motif is a nod to the Boita Bandana festival, where boats are floated every year in honour of Odisha’s ancient maritime history. It is also symbolic of the myth of Gajendra Moksha, where an elephant trapped in a river prays to Lord Vishnu and is rescued– a story of divine salvation.

Why is Horn Art Dying?

Despite it’s artistic value, the craft is struggling to survive the pressures of modern markets. Several issues endanger its future like:

- Legal Red Tape – The Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 has increased scrutiny on animal-derived products. Although horn is taken from natural deaths, artisans face police raids, confusion and harassment.

- Cost of Raw Material – The cost of obtaining horn legally has increased from ₹20/kg in 1980 to over ₹800/kg now. Most horn is exported abroad, leaving little for local crafters.

- No Marketing Muscle – While filigree art got a GI tag and Pipili got PMO visits, horn art was quietly buried under red tape and lack of storytelling.

- Youth Exit – Artisan’s children have moved on to IT jobs or migrated. As Purna Chandra Behera says: “I have seen my father and grandfather struggle in this for years, I will not continue to endanger my children’s future”.

What can be done?

Horn craft isn’t just a dying art, it is a lost opportunity. It is eco-friendly, lightweight, easy to ship, store and wear, and each piece is unique, unlike plastic or resin. There is still hope, but only if we act fast. Utkalika, the lone government body promoting horn craft, buys pieces from artisans– but that’s not enough.

What it truly needs is attention, in the form of:

- Design Revamp – The Government should step up to tie-up with NIFT/NID and create fusion products – horn and brass coasters, horn-inlay keychains, table decor and jewellery.

- Digital Retailing – Imagine if Lenskart launched a “Horn-Heritage” limited edition frame. Or if Okhai sold horn-inlaid home decor as “vegan vintage”. Or if FabIndia turned a corner of every store into an “Odisha Originals” section with horn art along with filigree and ikat.

Artisans don’t just need money. They need visibility. Branding. E-commerce. Design education. Social media storytelling.

Because if Forest Essentials can revive Ayurvedic Ghee for ₹5,000 a jar, surely Odisha can save horn by rebranding it as “India’s Ethical Ivory” – a craft that’s already sustainable, ethical and export-ready.

Conclusion: The Final Carving

Horn craft’s story isn’t just about bones and buffaloes. It’s about how tradition dies when no one updates its Instagram handle. It’s about fixing the gaping hole in our cultural economy where our ancient crafts are sinking. Because let’s be honest– Heritage can’t survive on sentiment alone. It has to adapt to changing times.

The tragedy isn’t just that this craft is dying. It is that they are dying quietly. Off-grid, offline, off-brand. While India sells yoga, Ayurveda and mangoes with global polish, horn art remains unpackaged and unprotected.

We often romanticise heritage, but let’s get real: Heritage without hustle is just a museum piece.

Craft needs commerce. Legacy needs logistics. And a motif needs a market.

If Odisha’s horn craft is to live, it can’t rely on fairs and folklore alone. It needs product designers who see the Makara as a brand mascot. It needs storytellers who can turn the Gaja Nauka into NFTs.

So the next time you sip chai from a kulhad or light a brass diya, spare a thought for the horn. It once carried Odisha’s pride on its back — shaped like a crane, carved like a poem, glowing amber in forgotten light.

All it asks now is for a future that is just as bright.

References

-

Das, M. (2015). Traditional Crafts of Odisha: A Socio-Economic Study. Odisha State Open University.

Retrieved from https://www.osou.ac.in/eresources/sociology-traditional-crafts-of-odisha.pdf -

Crafts Council of India. (n.d.). Horn and Bone Craft of Odisha. Retrieved April 28, 2025, from https://www.craftscouncilofindia.in

-

India Today Web Desk. (2019, September 6). Odisha’s horn crafts: A dying art with royal roots.

India Today. Retrieved from https://www.indiatoday.in/education-today/gk-current-affairs/story/odisha-horn-craft-1596628-2019-09-06 -

Ministry of Textiles, Government of India. (n.d.). Horn Bone Craft of Odisha. Retrieved from http://www.handicrafts.nic.in

-

Ghosh, S. (2020). Documenting the Disappearing Craft Traditions of India: A Case Study of Horn Craft of Odisha.

Indian Folklife, 75(2), 12–17. -

Odisha State Handicrafts Development Corporation (Utkalika). (2021). Crafts of Odisha: Horn Craft.

Retrieved from https://www.utkalika.in/horn-craft/ -

UNESCO Office New Delhi. (2013). Crafting a Future: Stories of Indian Women in Handicrafts.

Retrieved from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000229412 -

Roy, T. (2007). A History of Small-Scale Industries in India. Oxford University Press.

-

Pati, B. (2001). Identity, Hegemony, Resistance: Conversions in Colonial Odisha, 1800–2000.

Economic and Political Weekly, 36(3), 219–225. -

Tripathi, A. (2021). What a horn carving in Odisha tells us about craft, caste, and capitalism.

Scroll.in. Retrieved from https://scroll.in/magazine/996309/