There’s an English proverb that says, ‘Home is where the heart is’. Home holds within itself a sense of security, familiarity, and belonging. Mughal Delhi was loved dearly by its inhabitants and frequently personified by poets. However, near the end of the Mughal Empire, Delhi was frequently afflicted with instability and uncertainty. When the sense of order collapsed in Mughal Delhi, disrupted by violence, invasion, or sudden political change, poets found expression in a unique literary form to respond to this disorientation. The Shahr Ashob poetry is a reflection of the indestructible bond of the Dilliwalas with the place they called home.

falak zamin o mala’ik janab thi Dihli

bihisht o khuld men bhi intikhab thi Dihli

jawab kahe ko tod la jawab thi Dihli

magar khayal se dekha to khwab thi Dihli Delhi was a divine place

(Delhi was a divine place

It was distinguished even in the paradise

Delhi had no match; it was a unique place

But when we noticed it cautiously, it looked like a dream) (1)

~ Dagh Dihlavi

ORIGINS:

Shahr Ashob, or “city lamentation”, is a genre in Persian and Urdu poetry. The origins of ‘Shahr Ashub’ or ‘Shahrangez’ date back to the 11th and 12th centuries in Persia. Originally, the poetry featured a figure (usually a young craftsman) whose arrival in the city would cause a big stir. Masud Sa’d Salman (1121 AD) might have been the first to write a Shahr Ashob. According to Dr. Naim Ahmad (as cited by historian Rana Safvi on her blog), the genre was used in Persian and Turkish poetry as a source of intellectual entertainment, but in Urdu poetry, the genre took on a more somber temperament.

In Urdu, the genre reflected political, economic, and social disruption. The origins of Urdu Shahr Ashob can be traced back to the beginning of the 18th century. In addition to the Persian influences, the Urdu poems were meant to mourn the collapse of the city. This shift was brought about by the events of the 18th and 19th centuries, and the political and economic hardships that afflicted the city of Delhi.

18th CENTURY SHAHR ASHOBS:

دل و دلی دونوں اگر ہیں خراب

پہ کچھ لطف اس اجڑے گھر میں بھی ہیں

Dil-o-Dilli donon agar hain kharaab

P’a kuchh lutf is ujde ghar mein bhi hain

(My heart and my Delhi may both be in ruins

There are still some delights in this ravaged home.) (2)

– Mir Taqi Mir

Since the reign of Shah Jahan (1628-1658), Delhi became the capital of the Mughal Empire, both politically and culturally. Till the reign of the emperor Aurangzeb (1658-1707), the Mughals were a dominant power on the Indian subcontinent. However, by the early 18th century, Mughal rule had started to weaken. This diminishing of power resulted in Delhi experiencing massive destruction and plunder, owing to the invasion of the Persian Nadir Shah (1739). The devastation was a shock to the residents because of the immense scale of ruination, as well as the defeat of what was believed to be one of the strongest armies by the Persian forces in the Battle of Karnal. Along with this came the misery of the loss of livelihood and patronage.

According to Petievich, one of the first poems to be written in the grief of Delhi was probably by Shah Hatim Dihlavi (1699-1782). He was probably inspired by the Persian poet Sa’adi, who wrote, mourning the sack of Baghdad in 1258. The poets of Mughal India enjoyed considerable freedom of expression for their writing. Therefore, these poems also act as a primary source, contributing supplementary information through personal accounts that could not be found in the official records. For instance, according to the records, Nadir Shah’s invasion caused a famine in the city. Mir Taqi Mir (a nobleman before the invasion) writes about the state of hunger and humiliation:

“… with armed force they brought me to the city,

There my life took such a strange turn;

I had to ask someone for water, someone else for food.

Would that the hour of death had come to rescue me from that circumstance

I feared lest, should I remain living, my reputation be besmirched . . .“… Where I should not have gone I went a hundred times,

Weak with hunger, I went there with evil hands [i.e., to steal]

Being needy I went in search of bread. . . (3)

About the destruction, he wrote:

دلی پہ رونا آتا ہے کرتا ہوں جب نگاہ

میں اس کہن خرابے کی تعمیر کی طرف

dillī pe ronā aatā hai kartā huuñ jab nigāh

maiñ us kuhan ḳharābe kī ta.amīr kī taraf

(When I imagine the rehabilitation of Delhi

I mourn on this wasteland) (4)

-Mir Taqi Mir

Shahr Ashob was also a shift from the conventional style and topics prevalent in Urdu poetry of the time. However the poetic tradition was not completely rejected. The language used was colloquial Delhi Hindustani, heavily with the addition of Persian vocabulary. Mohammad Rafi Sauda wrote about the state of his beloved Shahjahanabad:

Jahanabad tu kab iss sitam ke qabil tha

Magar kabho kisi aashiq ka yeh nagar dil tha

Ke yun mita diya goya ke naqsh-e-batil tha

Ajab tarah se yeh bahr-e-jahan mein sahil tha

Ke jis ki khaak se leti thi khalq moti roll

(Jahanabad you were never deserving of such tyranny

You were once the heart of lovers, many

It was erased like a wrong letter by destiny?

T’was a one such shore in the ocean of the world

From whose dust people used to pick pearls) (5)

Following the widespread chaos and instability after the invasion, several people migrated to Lucknow for stability (and poets for patronage). But for some, Lucknow could never become what Delhi was. Mir Hasan wrote:

jab aya main diyar-e Lakhnau mein

na dekha kunh bahar Lakhnau mein

(When I got to the land of Lucknow

I didn’t witness any charm or delight in that state) (6)

In his final years, Mir wrote expressing his regret over migrating from Delhi to Lucknow:

خرابہ دلی کا وہ چند بہتر لکھنو سے تھا

وہیں میں کاش مر جاتا سراسیمه نہ آتا یاں

(Desolate Delhi was far superior to Lucknow

If only I hadn’t rushed here and had died there instead.) (7)

The following years were marked by the lingering effects of the devastation, coupled with another sacking of Delhi by Ahmad Shah Abdali (1757). Ghulam Ali Hamadani (‘Mushafi’) (1747-1824) was born almost a decade after the Nadir Shah invasion. He had to endure the aftereffects of the destruction and later the sack of Delhi by the Afghan forces. He wrote about the state of Delhi in his Kulliyat-e-Mushafi:

دلی ہوئی ہے ویراں سونے کھنڈر پڑے ہیں

ویران ہیں محلے سنسان گھر پڑے ہیں

dillī huī hai vīrāñ suune khañDar paḌe haiñ

vīrān haiñ mohalle sunsān ghar paḌe haiñ

(Delhi lies desolate, barren ruins remain,

Deserted are the neighborhoods, lifeless stand the homes.)

The poets were not just critical of their situation, but also criticised the actions of their rulers. A Shahr Ashob by Qaim Chandpuri harshly criticizes the measures taken by Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II in the Battle of Sarkartal in 1772.

Kaisa yeh Shah ke zulm pe uski nigah hai

Haathon se uske ek jahan dadkhah hai

Luchha ek aap saath looter sipah hai

Namus e khalq sa’e mein uske talab hai

Shaitan ka yeh zil hai naa Zill e Ilahi

(What kind of King is he who is intent on injustice?

An entire world is protesting against him

A lout himself, has a brigand army

The honour of the people is defiled by his rule

He is the shadow of Satan, not the shadow of God) (8)

19th CENTURY AND The Revolt of 1857:

تذکرہ دہلی مرحوم کا اے دوست نہ چھیڑ

نہ سنا جائے گا ہم سے یہ فسانہ ہرگز

tazkira dehli-e-marhūm kā ai dost na chheḌ

na sunā jā.egā ham se ye fasāna hargiz

(Don’t start the story of the deceased Delhi, O friend

We definitely won’t be able to bear hearing this story) (9)

–Altaf Hussain Hali

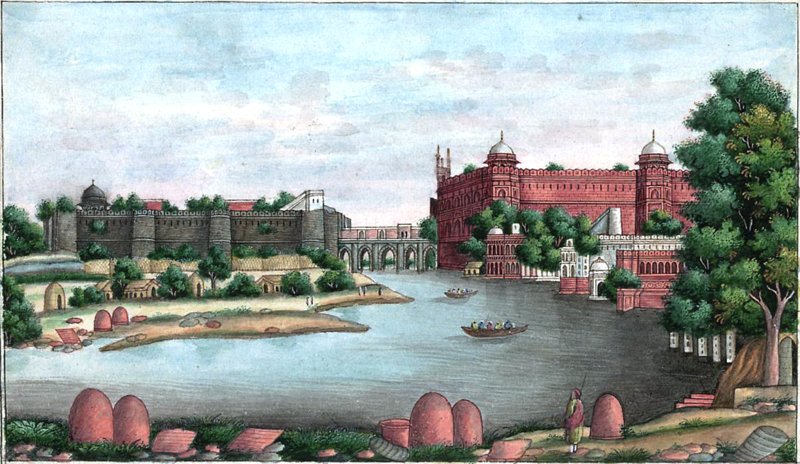

After the Battle of Karnal, Mughal power continued to be weakened. By the 19th century, the Mughal ruler had no effective political power at hand. But the court of the Mughal emperor thrived culturally. Till the time of the last Mughal ruler, Bahadur Shah Zafar, the Qila-e-Moalla (the Red Fort of Delhi) frequently hosted a large number of poets, writers, and artists. By the 18th and 19th centuries, Urdu poetry had taken its distinctive form and prospered in the city of Delhi. Many famous poets belonged to this time period, including Mir Taqi Mir, Sauda, Mirza Ghalib, Daagh Dehlvi, Mohammad Ibrahim Zauq, and even Bahadur Shah Zafar himself.

However, the 19th century brought another wave of destruction with it. The sepoys had captured Delhi and established Bahadur Shah Zafar as their head during the revolt of 1857. The British response was especially harsh. The Revolt had a devastating impact on cities like Delhi, Lahore, Agra, and Lucknow. Following the revolt, Indo-Muslim elites saw their world crumble, with many nobles imprisoned, executed, or expelled. Urdu poets portrayed 1857 as an apocalyptic event.

Ancient Sky, Delhi’s mortal enemy,

What did you gain when Dehli’s every trace was lost?

Alas that Shah Jahan’s building should be dug up!

Alas, for Delhi’s splendour has been razed.

Neither the Fort is there, nor its old street.

Why, then, should Delhites think Delhi is Heaven? (10)

~ Shahab al-Din Ahmad “Saqib”

The trauma was likened to Karbala, signifying a moral and cultural martyrdom. The poems compared “then” with “now”; “gardens” with “deserts”, “princes” with “beggars”, and a prosperous city with ruins. The city’s destruction was seen not just in terms of harm to its people, but also to its buildings and structures. Surviving structures symbolised hopes of cultural survival.

Thank God, the Jama‘Masjid remained standing!

There is now hope that it was saved, the life of Delhi. (11)

Even this time, the elites were left without their belongings. Destruction was accompanied by food shortages:

ہے اب اس معمورہ میں قحط غم الفت اسدؔ

ہم نے یہ مانا کہ دلی میں رہیں کھاویں گے کیا

hai ab is maamuure meN qaht-e Gam-e ulfat asad

ham ne yih maanaa kih dillii meN rahe khaaveNge kyaa

(there is now in this town a dearth scarcity of the grief of love, Asad

Granted that we would remain in Delhi – what will we eat?) (12)

~ Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib

Bahadur Shah Zafar was exiled to Rangoon in Burma. In his final days, Zafar wrote:

Kitna hai badnaseeb Zafar dafn ke liye

Do gaz zameen bhi na mili ku e yaar mein

(How unfortunate is Zafar, that even for his burial

He couldn’t get two yards of land in the beloved’s lane) (13)

Fughan-e Dehli (1863), translated as ‘The Lament for Delhi’ is a very important work regarding the Shahr Ashobs of Delhi. It is an anthology by Tafazzul Husain, containing 59 poems by more than 38 poets. The anthology has three theme-based divisions. The first contains four pre-1857 poems, the second features fourteen poems on 1857 in the musaddas form, and the third comprises thirty-eight ghazals and two qat‘ahs on the events of 1857. In recounting the events of 1857, Urdu poets conveyed a shared sense of cultural loss, framing themselves as a “people of suffering” (ahl-e dard).

گاہ جل کر کیا کیے شکوہ

سوزش داغ ہائے پنہاں کا

گاہ رو کر کہا کیے باہم

ماجرا دیدہ ہائے گریاں کا

اس طرح کے وصال سے یا رب

کیا مٹے دل سے داغ ہجراں کا

gaah jal kar kiyā kiye shikva

sozish-e-dāġh-hā-e-pinhāñ kā

gaah ro kar kahā kiye bāham

mājrā dīda-hā-e-giryāñ kā

is tarah ke visāl se yā rab

kyā miTe dil se daaġh hijrāñ kā

(Such inflaming is the complaint,

Alas, we bear this burning scar!

Jointly, alas, we cry and tell

The tear-shedding events witnessed.

Thus we meet with friends, O God,

How could we erase from our hearts the scar of separation?) (14)

~ Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib

CONCLUSION:

Shahr Ashob gave voice to the grief of those who watched the destruction of their city. It captured the anguish, loss, and disillusionment experienced during periods of political upheaval and social decline. Along with being important works of literature, these poems serve as an incredible source of history, enabling us to understand the lives of people. It tells us about the love and attachment of people to their homeland, the place where they belong.

TRANSLATIONS:

- So Yamane . (2000). Lamentation Dedicated to the Declining Capital: Urdu Poetry on Delhi during the Late Mughal Period. Journal of the Japanese Association for South Asian Studies, 12.

- https://juvenilia.video.blog/2019/03/18/dilli/

- Petievich, C. R. (1990). POETRY OF THE DECLINING MUGHALS: THE “SHAHR ĀSHOB.” Journal of South Asian Literature, 25(1), 99–110.

- So Yamane . (2000). Lamentation Dedicated to the Declining Capital: Urdu Poetry on Delhi during the Late Mughal Period. Journal of the Japanese Association for South Asian Studies, 12.

- https://www.sahapedia.org/shahjahanabad-shahr-ashob-poetry-and-the-revolt-of-1857

- So Yamane . (2000). Lamentation Dedicated to the Declining Capital: Urdu Poetry on Delhi during the Late Mughal Period. Journal of the Japanese Association for South Asian Studies, 12.

- Imaduddin. (2024). A poet’s lament for a lost city: ‘Dilli jo ek shahr tha aalam me intikhab.’ INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INNOVATIVE RESEARCH IN TECHNOLOGY, Volume 11(Issue 5), 843–847.

- https://ranasafvi.com/the-lost-art-of-urdu-poetry-shahr-ashob-was-a-lament-for-a-city/

- https://juvenilia.video.blog/2019/03/18/dilli/

- https://ranasafvi.com/shahr-ashob-by-saqib-after-1857/

- TIGNOL, E. (2017). Nostalgia and the City: Urdu shahr āshob poetry in the aftermath of 1857. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 27(4), 559–573.

- https://juvenilia.video.blog/2019/03/18/dilli/

- https://www.sahapedia.org/shahjahanabad-shahr-ashob-poetry-and-the-revolt-of-1857

- TIGNOL, E. (2017). Nostalgia and the City: Urdu shahr āshob poetry in the aftermath of 1857. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 27(4), 559–573.

REFERENCES:

- https://www.rekhta.org/

- Petievich, C. R. (1990). POETRY OF THE DECLINING MUGHALS: THE “SHAHR ĀSHOB.” Journal of South Asian Literature, 25(1), 99–110.

- So Yamane . (2000). Lamentation Dedicated to the Declining Capital: Urdu Poetry on Delhi during the Late Mughal Period. Journal of the Japanese Association for South Asian Studies, 12.

- TIGNOL, E. (2017). Nostalgia and the City: Urdu shahr āshob poetry in the aftermath of 1857. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 27(4), 559–573.

- https://www.rekhta.org/poets/mushafi-ghulam-hamdani/profile

- https://www.sahapedia.org/shahjahanabad-shahr-ashob-poetry-and-the-revolt-of-1857

- https://memorients.com/articles/textualising-the-nostalgia-of-1857-the-shahr-ashob-genre

- https://ranasafvi.com/the-lost-art-of-urdu-poetry-shahr-ashob-was-a-lament-for-a-city/

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/etimes/trending/how-did-one-battle-in-1739-shatter-the-mughal-empire-the-story-you-need-to-know/articleshow/118609171.cms