Introduction

The former colonial trading outpost and now the financial capital of India i.e. Mumbai is known for abundant imperial architecture. Early 19th century colonialists were heavily influenced by the debates on architecture back in their mother country and applied those discourses in erstwhile Bombay. In the 19th and 20th centuries, British administration in India transformed the city of Mumbai with rigorous urban planning. These buildings and elements of architecture stood to represent the grandeur of their colonial rule in India. The eminent classification of a cluster of buildings of Bombay as UNESCO World Heritage Site has given a rejuvenated outlook to these imperial architectural structures. According to UNESCO, there are broadly four primary categories of architecture styles in Mumbai: Victorian Gothic, Neoclassical, Art Deco, and Indo-Saracenic. Additionally, it has deemed Mumbai as one of the largest sites vis-a-vis area, containing 92 buildings spread out in an area of almost 67 hectares.

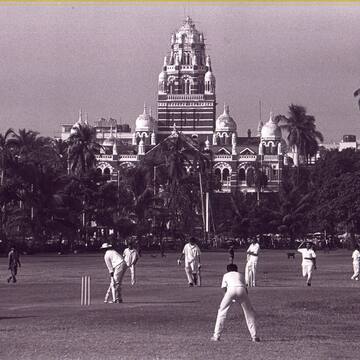

The overarching influence of these architectural styles nudged the colonialists to refer to Mumbai as Urbs Prima Indis i.e. the first city of India. In the aforementioned architectural themes, Victorian Gothic and Art Deco became the most widespread and discussed. There were two phases of urban development in Mumbai in the 19th-20th centuries: the first phase was the construction of Gothic architecture and Oval Maidan in the 1880s and the second phase with the Backbay Reclamation Scheme which embraced Art Deco style in the early 20th century.

Victorian Gothic Style

The shaping of Bombay’s cityscapes to Victorian Gothic was under the governorship of Frere. Being a bustling port and melting pot of local immigration, Bombay inhabited citizens who actively were a part of financial and private affairs—giving colonialists a “less colonial” sentiment. The Universities of Bombay especially were constructed via these public-private enterprises between Indian merchants and European agencies. The Rajabai Tower, Convocation Hall, and the library building of the University of Mumbai campus reflect a style not entirely European, not completely Indian—something labeled as ‘Gothic Revival.’ The Gothic style of architecture in Western Europe was characterised by flying buttresses, rib vaults, large windows and elaborate tracery.

George Scott of London was the pioneer of designing these neo-gothic architectural edifices. Scott’s designs were considered too expensive for the available budget, leading the assistant architects to the Government of Bombay, to be brought in to fit more comfortably within the financial constraints. This style is deeply embedded in Christianity, with University of Mumbai’s rose tinted windows and pointed arches, it seems that the biblical parts were carefully excluded but nonetheless the style was inspired. Mumbai’s Gothic edifices rose from local geology, apart from stained glass and minted tiles from England, golden stone, limestone, and graphite were sourced from Kurla, Porbandar, and Ratnagiri.

Christian Eclecticism to Secularisation

G. Scott’s design plan for Senate Hall of University of Bombay and Rajabai Tower. For the Senate Hall, he was inspired by the English Gothic style that emerged during the Crimean Church debate. The University library building with its lacy arcades and stonework supporting polychromatic masonry was a direct transfer of the arcade on the Doge’s Palace from Venice of the 14th century. The Rajabai Tower was inspired by Giotto’s Campanile in Florence from 1334. This Gothic style of stone iconography, pointed arches, and biblical ornaments in imperial Bombay were ‘secularised’

without losing their original character. For Scott, these edifices had a non-religious purpose only. The stunning rose window of the Convocation Hall, unlike European cathedrals which usually depicted scenes of Christ surrounded by the 12 apostles, here twelve zodiac signs take the place of the Christian images, transforming religious elements into something more widely distributed. The Rajabai Tower instead of ornate niches of European saints and monarchs, the tower portrays sculptures of the 24 castes from Western India. These figures include a Rajput with sword, a devotional Parsee, and a Kutchi merchant, forming an Indian cultural ethos.

Art Deco Style

In Mumbai there are 76 edifices defined as Art Deco structures stretched across SP Mukherjee Chowk, Oval Maidan, and Marine Drive—making it the second largest Art Deco city after Miami, USA. In the 1920s, Art Deco took its inception in Europe with pyramidical structures, chevrons, zig-zigs, florals with modern geometric elements. In the 1930s, prominent Indian industrialists such as Shiavax Cambata, K.A. Kooka, and Framji Sidhwa commissioned the construction of Art Deco buildings in Mumbai. These adorn Marine Drive and the western side of Oval Maidan were among the first created by a fresh wave of Indian architects, including Gajanan Mhatre, Sohrabji Bhedwar, and P.C. Dastur. These were primarily residential buildings with uniform height, open balconies and high ceilings.

The Backbay Reclamation Scheme was an impactful undertaking in the 1920s to extend the peripheries of a landlocked city, and was visualised as a space that would be a welcome escape from the other congested spaces. This initialised as an elitist venture soon spread out to the sub-urban areas, Dadar, Sion, and Matunga. According to Michael Windover (associate professor in the School for Studies in Art and Culture at Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada), the rich builders rented these edifices out to the migrants which helped in releasing rigid caste boundaries and embracing the cosmopolitan environment of Mumbai.

Pop Culture Symbiosis

Major artists and filmmakers have ventured out to pay homage to these distinct architectural elements of Art Deco Bombay and Victorian Gothic themes. Anurag Kashyap created Bombay Velvet (2015), and portrayed the glamorous port city with Deco-style clubs, trams, and lanes to evoke the modernity of retro Mumbai. The Marine Drive promenade in Wake Up Sid (2009) and the majestic Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus in Ra.One (2011), shows how these sites work not merely as background to art pieces but as active parts.

Conclusion

The ‘Old Bombay glamour’ so popular in visual culture and media has got a lot to do with the Victorian Gothic and Art Deco ensemble of Mumbai. These architectural styles depict a by-product of European and Indian values over the colonial period, which have gradually evolved to be labeled as a pleasant and much-loved aesthetic settings for not just academic, but other purposes. However, the imperial and colonial legacy harboured by these architectural edifices should be studied and known since no art form exists in vacuum—it’s always in a reciprocal relationship with its material, social, and cultural ambiences.

References:

Dalvi, M. (2022). Tracing the Gothic Revival in Bombay through the Architecture of the University Buildings. In Tekton: A Journal of Architecture, Urban Design and Planning (Vol. 9, Issue 2, pp. 8–25). https://tekton.mes.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/9.2-R-Mustansir-Dalvi.pdf

Art Deco Mumbai Trust. (n.d.). Know the art deco history of Mumbai. The Hindu. https://www.artdecomumbai.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/The-Hindu-October-2023.pdf

Mitra, S. (2025, September 13). Gothic in Translation: Architectural adaptation in Colonial Bombay. MAP Academy. https://mapacademy.io/bombay-gothic-colonial-architecture-in-bombay/

Nandwani, D. (2021). Mumbai’s nod to the art deco movement. In CoverStory. https://www.artdecomumbai.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Khabar-Bombay-Deco.pdf

Victorian Gothic and Art Deco Ensembles of Mumbai. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1480/