Introduction

India’s architectural legacy is diverse, with the varied geography and culture. From stone temples of the South to bamboo structures of the Northeast, architecture is marked by its responsiveness to materials available, terrain and climate. These architectural structures are not only functional and sustainable but also showcases the aesthetic and community life of HImachal. With many contributions to the architectural history of Himachal Pradesh, Kath-Kuni stands out for being sustainable and for structural resilience. It is an example of mountain architecture which is deeply local and adapted to its environment. It is named after two primary materials used, kath(wood) and kuni(stone). This style is seen in the areas of Shimla, Chamba, Kinnaur and Mandi. More than just an architectural style, Kath-Kuni is a living tradition. In an age of steel and concrete, this traditional technique reminds us of the strength of the local building practices.

History

The word Kath-Kuni is derived from the Sanskrit words ‘kashth’ for wood and ‘kona’ for corner. This technique combines stone and wood placed in alternating layers without the use of mortar. This style of building became popular as the region was abundant with Deodar wood, which was known for its strength and resistance to decay and insects. The earliest known use of this construction was linked to temple architecture. Many of such structures were commissioned by local rulers and wealthy landowners to build temples, which were religious and community centers. The Hadimba Devi Temple in Manali and Naggar Castle are early examples of this.

Over the period of time, this style of architecture spread and became an integral part of the Himachali rural life. Houses and temples were built using this technique and artisans, such as suthars(carpenters) and mistris(masons), refined this craft with knowledge that was passed down to them. Additionally, the abundance of resources, like the Deodar forests, also helped in making this tyle of construction popular. The architecture was adapted to the snowy climate: where a steep roof prevented snow from accumulating, thick walls for insulation and wooden verandahs for people to interact. These structures were not only strong but also aesthetically pleasing. There were carved wooden brackets, lattice windows and slated roofs which showed the craftsmanship.

Constructing Kath-Kuni

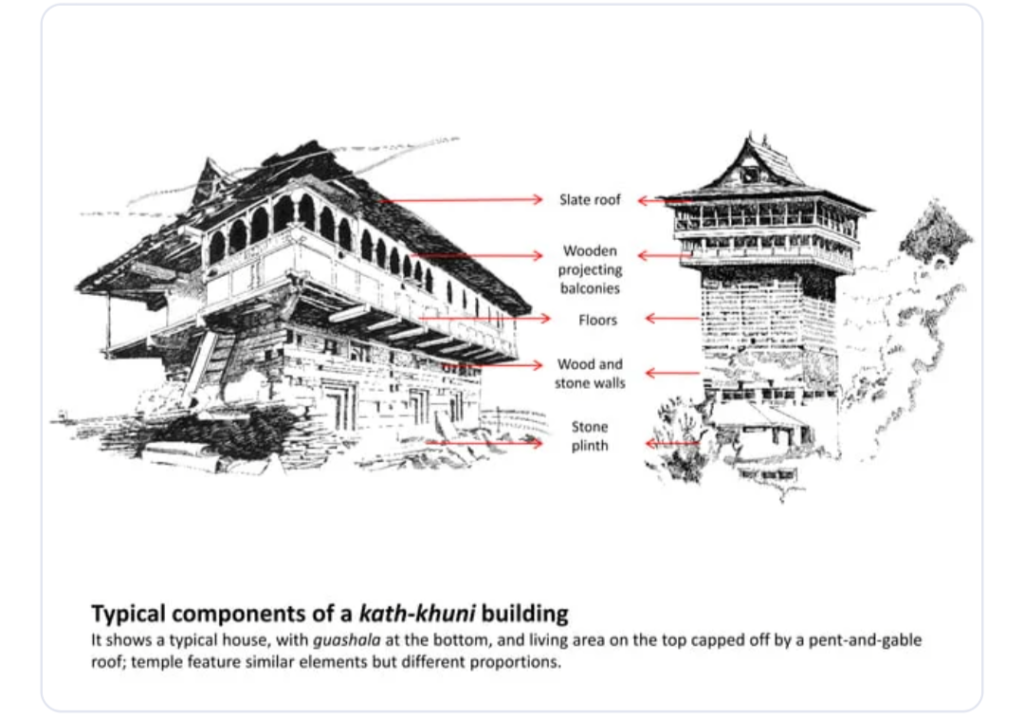

To construct a Kath-Kuni structure is a carefully planned and labour-intensive task. Wooden beams are interlocked and crisscrossed at the corners which form a strong framework. Stones are dry stacked between the wooden bands, creating a composite wall, which can withstand both snow and earthquakes, which is needed as the region is seismically active. The wooden bands are joined using the techniques of wooden pegs and dovetail joints. The walls were thick and solid for keeping the interiors cooler in summer and warmer in winter. The roofs were steep and are made of slate tiles, which made rain and snow slide down easily.

Small, deeply set windows are added for insulation, while verandahs and balconies are constructed with decorative wooden brackets.

There are carvings made on the doorframes, ceilings and pillars which showcase the skills of local artisans. Most of the Kath-Kuni houses are multi-storied: the ground floor is generally used for cattle or storage, the middle floor for grains and the top floor is for the people to live.

Style and Ornamentation

What makes Kath-Kuni special beyond its strength, is the attention to beauty. Skilled wood carvers called the ‘suthars’ add in the detailed carvings to the doors, balconies, wooden frames and pillars. We mostly see carvings of flowers, vines, gods and goddesses, even a few of the temples have lotus or mandala carved into the ceilings. Animal motifs such as the elephants, lions and birds are seen to symbolise strength and wisdom. There are also celestial symbols like the sun and the moon in the temple carvings showing the sacred nature of the space.

One of the noticeable features are the jharokhas (windows), which were supported by carved wooden brackets and spindles. Another interesting fact is that these wooden joints and stonework are left as it is and are not covered or painted, which add a rustic vibe to the architecture. One can clearly see the layers of stone and wood, which add an extra dimension to the beauty of these buildings.

Iconic Structures

One of the most iconic Kath-Kuni architecture is Hadimba Devi Temple, built in the 16th century. It is a multi-storied structure, comprising pagoda-style roof with an intricately carved entrance showing the spiritual symbolism with structural unity. It has a four-tier pagoda-style roof and carvings on doorways, walls and beams depicting scenes from mythology, floral and animal motifs as well.

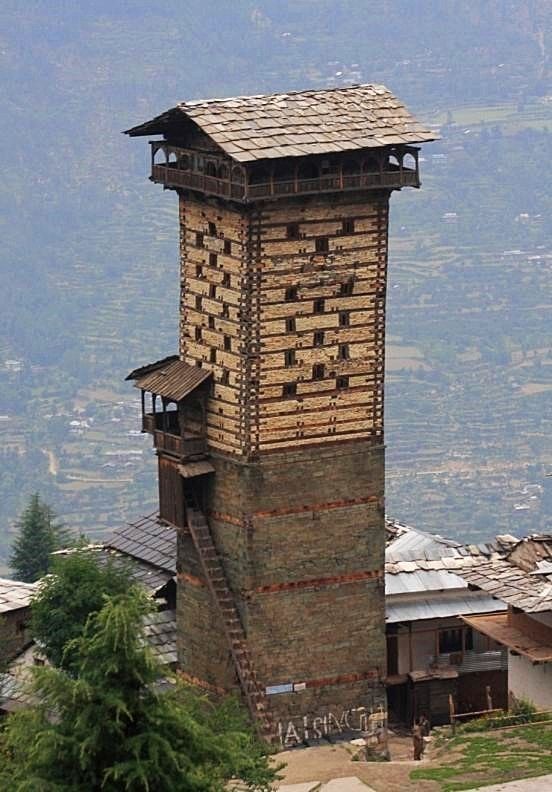

Another is Chehni Kothi in Banjar Valley, which is a 12-story temple-fort. Originally built as a fort by the local rulers, is now one of the tallest traditional structures in the region. The thick walls and precision in the joinery have helped it to stay intact, withstanding numerous earthquakes.

Naggar Castle, built in the 15th century, is also another prominent surviving example. This construction has open courtyards, a temple and richly ornamented windows. Today, it is converted into a heritage hotel, managed by Himachal Tourism, preserving the architectural legacy.

Current Status

In recent years, Kath-Kuni architecture has faced challenges due to the rise of concrete buildings and the loss of traditional knowledge. The modern construction is fast and cost-efficient, compared to the traditional architectural process. The deforestation laws have limited the access to Deodar wood, making it expensive and less accessible. Yet, recognition is given there to value this architectural heritage by the government. NGO’s and the tourism department have begun to promote and preserve the Kath-Kuni buildings. Institutions like INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage) have documented and restored a few of these buildings. There are architects like Rahul Bhushan, who are trying to revive and incorporate the Kath-Kuni elements in the modern-day architecture. Eco-tourism and heritage homestays have also created incentive to renovate and retain these traditional buildings. Also, some architects have begun to integrate the Kath-Kuni features into contemporary designs, giving a balance between tradition and modern needs.

Conclusion

Kath-Kuni stands as a remarkable example of traditional building practices. The use of locally sourced materials and sustainable nature shows the connection with nature. The beauty, functionality and adaptability offer lessons in sustainable architecture. What truly sets Kath-Kuni apart, is the blend of engineering and artistry. The wooden joints, decorative wood carvings and cultural motifs are not just ornamental, but symbolic to the communities that live and built them which is also a reflection of their life in Himachal.

With climate change and urban expansion, Kath-Kuni stands as a model of ecological and cultural sustainability. Preserving and promoting this architecture, is not just about safeguarding old buildings but to revive the ways of thinking, which values community, craftsmanship and coexisting with nature.

References

https://www.architecturaldigest.in/content/himachal-pradesh-traditional-kath-kuni-architecture/

https://www.sahapedia.org/the-himalayan-vernacular-kath-khuni-architecture#:~:text=The%20widespread%20technique%20of%20kath,free%20standing%20granary%20in%20Chitkul.

https://indianexpress.com/article/et-al-express-insight/the-kath-kuni-revivalist-an-architect-on-a-mission-to-restore-himachals-traditional-architecture/